The Coronation in Context

On February 24, 1530, Pope Clement VII crowned Charles Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor in the

Basilica San Petronio in Bologna. It was the last time a pope would crown an emperor, ending a

700-year-old tradition that began with Charlemagne's coronation on Christmas Day in 800.

Amid increasing power of the Ottoman Empire to the east, the subjugation of the New World to the west, and the rise of Protestantism within Europe itself, the political situation was delicate. Charles could not be crowned in Rome, because Protestant German mercenaries he employed in a conflict with France had sacked the Eternal City three years earlier.

This context informed the planning and execution of the ceremony, which had to conform to tradition but also reflect the political realities of the day. For the newly-crowned Charles V and Pope Clement, the coronation signified a continuation of an idealized, united, Christian European state that had its origins in the Roman Empire itself.

Amid increasing power of the Ottoman Empire to the east, the subjugation of the New World to the west, and the rise of Protestantism within Europe itself, the political situation was delicate. Charles could not be crowned in Rome, because Protestant German mercenaries he employed in a conflict with France had sacked the Eternal City three years earlier.

This context informed the planning and execution of the ceremony, which had to conform to tradition but also reflect the political realities of the day. For the newly-crowned Charles V and Pope Clement, the coronation signified a continuation of an idealized, united, Christian European state that had its origins in the Roman Empire itself.

The Holy Roman Empire was an idealized re-establishment of the realm of Charlemagne, the Frankish ruler whose territories corresponded roughly to those of modern France and

Germany. In the year 800, Protestantism the office of the pope; succession or line of popes;

the system of government of the Roman Catholic Church of which the pope is the supreme head

Charlemagne came to the aid of Pope Leo III, who had run afoul of the nobility in Rome. He

convened a council in Rome that affirmed Leo's papacy Papacy: The office of the pope; succession or line of popes; the system of government of the Roman Catholic Church of which the pope is the supreme head on December 1. In return Leo crowned Charlemagne “Emperor of the Romans” in Old St. Peter's

Basilica in a Mass on Christmas Day, reserving for Charlemagne (now Charles I) the role of defender

of Rome and of the Church.

Tap to Flip

Tap to Flip

After Charlemagne's death, disputes over power among his grandsons led to the precipitous

decline of the dynasty. For nearly a century the title went unclaimed, but was revived in

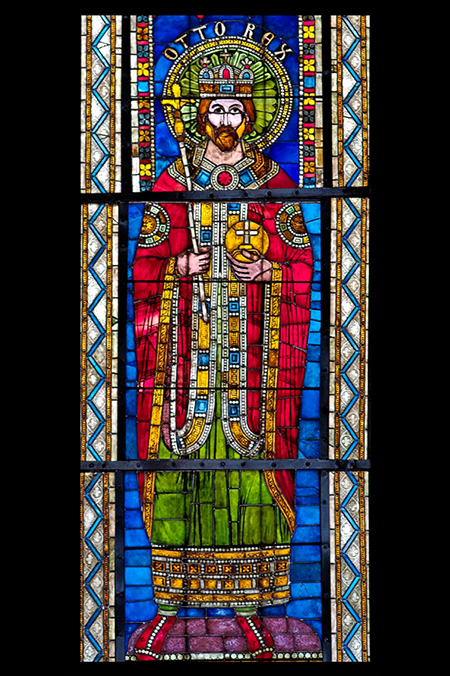

962 when Otto I, the elected King of the Saxons, was once again crowned

Emperor of the Romans by the Pope in Rome. Otto's coronation forged a centuries-long special

relationship between the Papacy, the memory of Ancient Rome, and the consolidated Germanic

realm–a “Holy Roman Empire.”

Dual Coronations

Symbolically and politically, this relationship was marked in two coronations. The first

was a royal coronation as King of the Germans by the ducal Ducal: The office of the pope; succession or line of popes; the system of government of the Roman Catholic Church of which the pope is the supreme head electors in Charlemagne’s old capital, Aachen. The second was an imperial, or papal, coronation

as Emperor of the Romans in Rome under the pope’s hand. From 962 until 1530, in principle

each ruler of the Holy Roman Empire was to receive both a royal and an imperial coronation.

zoom_in

zoom_inVR recreation of the wooden platform in San Petronio

During these five and a half centuries, these dual coronations served to ease two

important political tensions: the role of the German electors in choosing their leader

versus traditions of primogeniture Primogeniture: An exclusive right of inheritance belonging to the eldest son and the role of papal, or sacred, power versus imperial, or secular, power. While every

Christian coronation ceremony aims to affirm the new monarch’s power as God-given, the

particular tension between these political elements in the German realm made such an affirmation

of paramount importance. These twin ceremonies were thus charged with meaning, elevating

the emperor as the primary defender of the Christian faith, just as Charlemagne had been.

©